Hybrid Acoustics and the Ergonomic Renaissance of the Neckband

In the rapidly evolving landscape of personal audio, the narrative has been dominated by the meteoric rise of “True Wireless Stereo” (TWS)—the tiny, bean-sized earbuds that float in our ears, untethered by any wires. They represent the apex of miniaturization. Yet, in engineering, miniaturization often comes with compromises: smaller batteries, smaller drivers, and compromised antenna placement.

Amidst this sea of plastic beans, a counter-trend has persisted and arguably matured into a superior form factor for the pragmatic user: the Neckband. Devices like the Muitune i35-JPO represent the renaissance of this design philosophy. By refusing to shrink everything into the ear canal, they unlock physical space for superior acoustic architecture—specifically, the Hybrid Driver System—and offer an ergonomic solution that respects human anatomy.

This article explores the deep physics behind blending different driver technologies (Hybrid Acoustics) and the biomechanical advantages of the neckband form factor. It is a study of why sometimes, a little bit of wire is not a tether, but a lifeline to better sound and comfort.

The Physics of Hybrid Drivers: A Sonic Marriage

The holy grail of loudspeaker design is a single driver that can reproduce the entire audible frequency spectrum (20Hz to 20kHz) with equal linearity and power. Physics, unfortunately, makes this nearly impossible.

To produce deep bass (low frequency), a driver needs to move a large volume of air. This requires a large surface area (diaphragm) and a long excursion distance. Such a driver is inherently heavy and slow.

To produce sparkling treble (high frequency), a driver needs to vibrate thousands of times per second. This requires near-zero mass and extreme rigidity to stop and start instantly (Transient Response).

A single driver trying to do both often results in “Intermodulation Distortion”—the heavy bass movements distorting the delicate treble vibrations.

The Dynamic Driver: The Bass Piston

The Muitune i35-JPO solves this via a Hybrid System. First, it employs a 10mm Neodymium Dynamic Driver. This is the “Subwoofer” of the system.

The physics here is simple: Volume Displacement. A 10mm diaphragm has significantly more surface area than the 6mm drivers found in many TWS buds. When energized by the neodymium magnet, it acts like a piston, pushing a substantial column of air down the ear canal. This physical movement of air is what we perceive as “punchy” bass. It is visceral; you can feel the pressure change.

The Balanced Armature: The Treble Scalpel

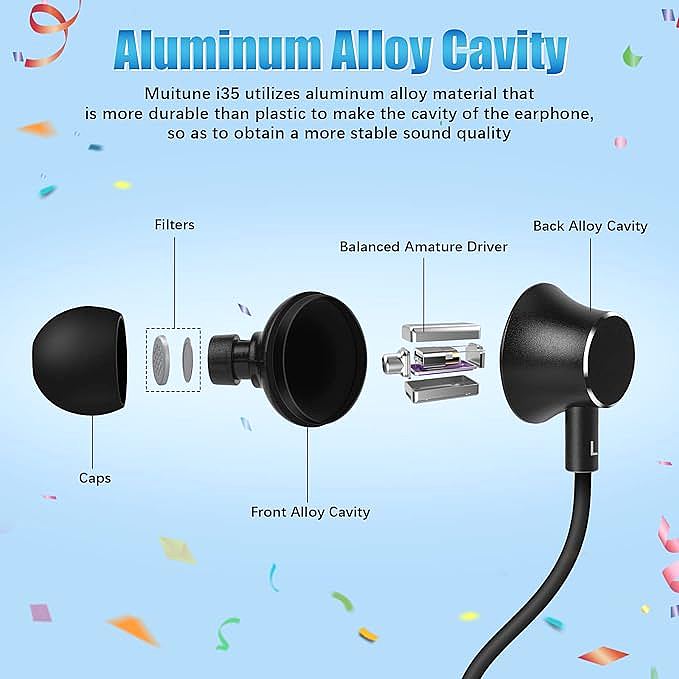

For the mids and highs, the i35-JPO hands the baton to a Balanced Armature (BA) driver. Originally developed for hearing aids, BA drivers are masterpieces of precision engineering.

Inside a BA, a tiny reed is balanced between two magnets. There is no heavy voice coil attached to the diaphragm. Instead, a drive pin transfers the vibration. Because the moving parts are vanishingly light, they have almost Zero Inertia. They can accelerate and decelerate instantly. This allows them to trace the intricate waveforms of high-frequency sounds—the breath in a vocal, the decay of a cymbal—without “smearing.”

By combining these two, the i35-JPO achieves Spectral Separation. The dynamic driver handles the heavy lifting of the low end, while the BA driver paints the fine details of the high end.

The Crossover: The Traffic Controller

Crucial to this marriage is the Crossover. This is an electronic circuit (or sometimes an acoustic filter) that splits the incoming signal. It directs low frequencies to the Dynamic Driver and high frequencies to the BA. A well-designed crossover ensures that the two drivers don’t fight each other in the midrange, creating a seamless “coherence” where the listener cannot tell where one driver stops and the other starts.

Material Science of the Chamber: Aluminum Alloy

The housing that contains these drivers is not merely a container; it is an acoustic component. The i35-JPO features an Aluminum Alloy Cavity. Why choose metal over cheaper, lighter plastic?

Resonance and Coloration

Every physical object has a “Resonant Frequency”—a pitch at which it naturally wants to vibrate. If a speaker cabinet vibrates along with the music, it adds its own sound to the mix. This is called Coloration. Thin plastic shells often resonate in the lower-midrange, causing a “boxy” or “muddy” sound.

Aluminum alloy is significantly more rigid and dense than plastic. Its resonant frequency is pushed much higher, often outside the audible range or into a range where it is easily damped. This Acoustic Inertness ensures that the sound you hear comes purely from the drivers, not the casing.

Standing Waves

The internal shape of the cavity also matters. Sound waves bounce around inside the shell. If the walls are parallel and smooth, “Standing Waves” can form, amplifying certain frequencies and cancelling others. The precision machining possible with aluminum allows for complex internal geometries that break up these reflections, resulting in a cleaner, more linear output.

The Ergonomics of Weight Distribution: The Neckband Advantage

Beyond acoustics, the Neckband Form Factor offers a superior solution to the problem of Weight Distribution.

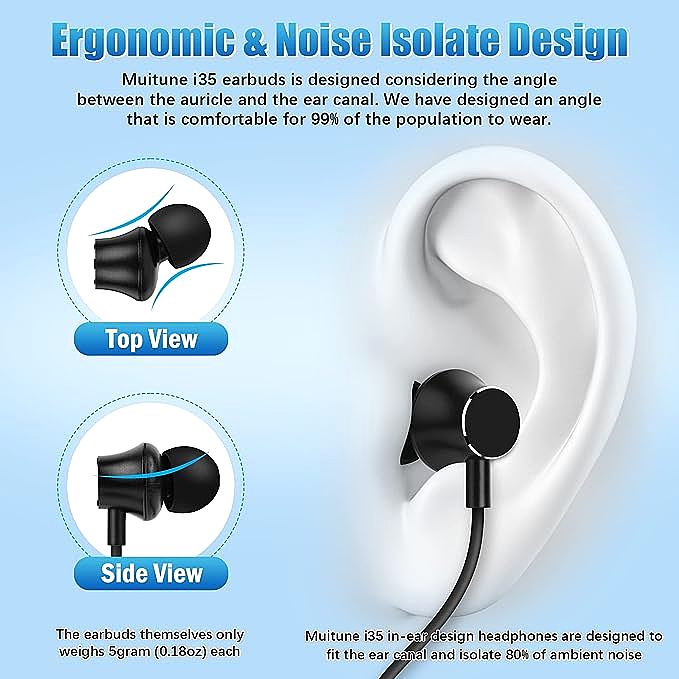

In a TWS earbud, everything—battery, Bluetooth chip, antenna, driver—must hang from the ear canal. The human ear canal is sensitive, lined with thin skin and nerves (the Vagus nerve branch). Supporting 5-7 grams of weight solely by friction against the canal wall leads to “Ear Fatigue” and physical soreness over time.

The Clavicle Anchor

The i35-JPO weighs 140 grams total, but the earbuds themselves weigh less than 2 grams. Where is the rest of the weight? It is resting on the Neck and Clavicle (Collarbone).

The neck and shoulders are structural weight-bearing parts of the body. They can support a few ounces indefinitely without fatigue. By offloading the heavy components (the massive 1000mAh battery and circuit boards) to the neckband, the part that actually enters your ear becomes featherlight. This is why neckband headphones are often preferred for all-day wear, marathon flights, or long shifts. The user gets the benefit of a massive battery without the penalty of heavy ears.

The Physics of Stability

Furthermore, the wired connection between the band and the buds acts as a safety tether. If a TWS bud falls out, it tumbles to the ground (or down a drain). If a neckband bud falls out, it simply drops three inches and hangs on your chest. For active users—cyclists, runners, warehouse workers—this Mechanical Security is invaluable. It eliminates the “anxiety of loss” that plagues TWS users.

Magnetic Utility and Digital Hygiene

Finally, the i35-JPO incorporates Magnetic Earbuds. This feature utilizes the Hall Effect (or simple ferromagnetism) to snap the backs of the earbuds together when not in use.

This transforms the device from a piece of tech into a piece of Apparel. When snapped together, the headset forms a closed loop—a necklace. It cannot slide off the neck. This “Always-Ready” state is functionally superior to TWS for intermittent use.

* TWS Workflow: Take case out of pocket -> open case -> take buds out -> put in ears -> listen -> take out -> put in case -> put case in pocket.

* Neckband Workflow: Pull buds apart -> put in ears -> listen -> snap together -> drop on chest.

The reduction in friction and steps makes the neckband the ultimate tool for people who need audio intermittently throughout the day—taking calls, listening to notifications, or brief interactions—without the fumble-factor of a charging case.

In conclusion, the Muitune i35-JPO demonstrates that older form factors often persist for a reason: they work. By combining the acoustic superiority of Hybrid Drivers with the ergonomic genius of the Neckband, it offers a high-fidelity, high-endurance alternative to the TWS hegemony. It is a device for the “Prosumer” who understands that physics cannot be cheated—that big sound needs big drivers, and long life needs big batteries, and the best place to carry that power is on your shoulders, not in your ears.